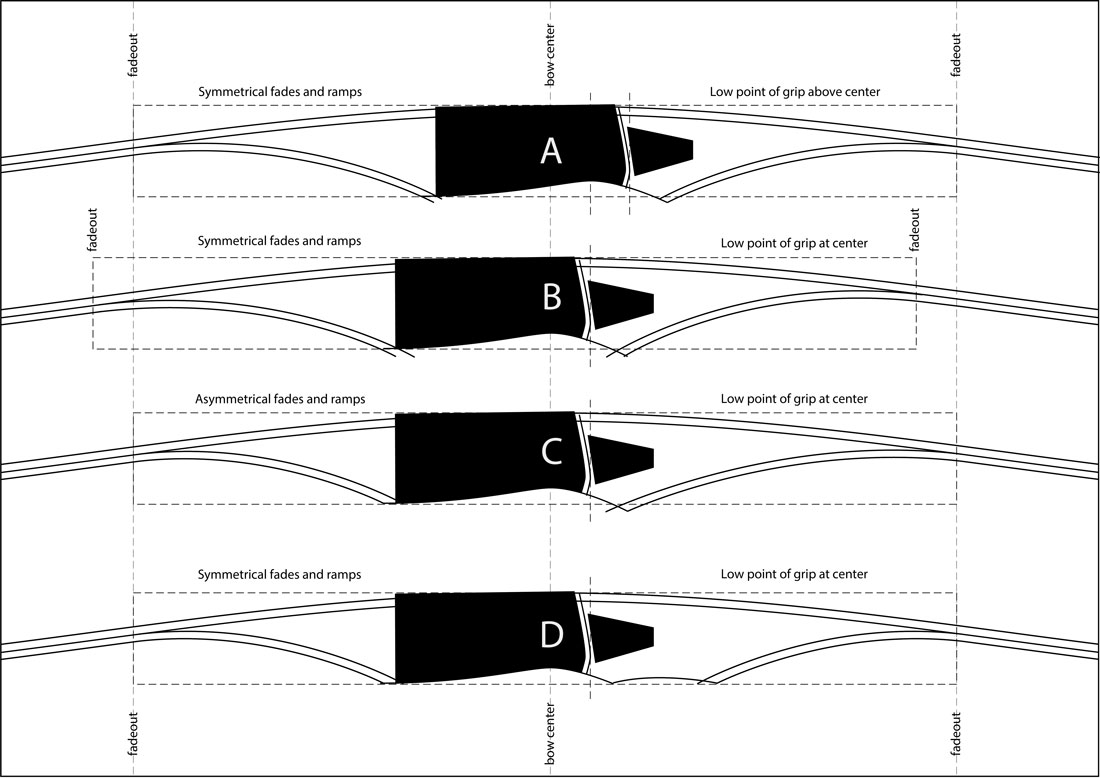

I’ve experimented with making longbows with four different riser layouts. Riser A represents probably the…

Splitting an osage log into bow staves

A straight Osage Orange log is like a log of gold to a selfbow bowyer. As you probably know, Osage trees don’t usually grow very straight, so finding a clean, straight one is a rare find. My friend Brent brought one over to my house this weekend for us to split into staves. It was about eight-to-10 inches in diameter at the base and almost perfectly straight! He cut it down on his farm in northern Boone County, Missouri, and he wants to make a bow out of it since it grew on his property. That’s pretty neat. If he doesn’t get one made, then hopefully I can make one for him. I hope to make one or two out of it, too. 😉

This will be his first bow build, so I am encouraging him to make one by himself. Osage orange is really nice bow wood. It is rough and tough, and really forgiving wood for a first-time bowyer.

The hedge tree was growing next to the road so he had to top it out first before dropping it so it wouldn’t completely block traffic in the road when it came down. This caused it to split out at the top end of the log, plus it had a really big knot next to the split which limited the number of full-length staves we were able to get out of it. It was about eight feet long and really clean.

We started the splitting process by looking over the base end really closely for natural splits and cracks. There were a couple of small cracks in the very middle of the log. I think one fun thing about splitting a log is trying to guess the way it will tend to naturally split. I’ve cut quite a bit of firewood, so it seems almost instinctive to look at a log and know how it will open up. After making guesses as to the best place to put the wedge, we started by tapping one wedge into the very end of the base of the log. Then I gave it a slam with the sledge hammer and the log popped right in half. Very nice. Then we put the second wedge in about two feet down the log and drove it in until the log opened up enough for the first wedge to come loose. As the crack opened up and extended further down the log, we continued leap frogging the wedges down the tree trunk and driving them in until the log was completely split in half. After that, we split those halves into quarters. Splitting a log into staves is similar to splitting logs for a split rail fence. You start on one end and split it from one end to the other. If you try to start in the middle, your wedges will get stuck in the wood and you won’t be able to continue.

I lost count after putting them back into the truck, but we ended up with a few full-length staves and several half staves that can be spliced together at the handle to make a bow.

Brent took them home and planned to coat the ends with polyurethane varnish so they won’t crack. After that dries, he will spray the wood and bark with insecticide to keep the wasp larvae from chewing holes in the wood. The bark will be left on until the staves are dry and ready to be worked down into bows.

Brent said this this tree was growing in kind of a low spot that was a little swampy. I guess that explains why it had pretty nice growth rings. It must have gotten plenty of water.

I did polycoat the ends and sprayed them down with insecticide. Ps gus liked the picture with me and macy he was getting jelous.

Very nice! Those staves should be ready in a couple of years?

awesome.

What time of year do you cut the ossage orange tree down Winter -summer ?

The primitive experts say it is best to cut bow staves in the winter because more of the sap is down out of the tree. For osage, leave the bark on the staves and split them into about 3″ wide splits. Make sure to seal the ends with shellac, wood glue, or other good paint sealer. This forces the moisture to escape out through the splits and not on the ends which causes cracks.

Thanks for the information

Regards Peter Emerson

Thanks for this guide Jim. I’d been trying to figure out something to do to make use of a large (14-18″ diameter) osage orange I cut down this Spring. It sounds like I should go ahead and cut it into 8′ sections and then split those, seal the ends and let them dry for a while. This tree was particularly interesting to fell because when I cut into it with the chain saw it was like someone turned on a water faucet. I think I could have filled a few two liter bottles with the volume of liquid that came pouring out. Interestingly my osage orange or bodark came from my back woods here in Bois D’Arc Missouri.

A few tips that may help you minimize losses; always start your wedge on the big end, as close to center as possible. If you try splitting a 1/4, a 1/2, or a whole log/post into 1/3’s (or one big, one little stave) more than likely it’ll run out and you quickly realize you ruined half of your stock. It’s easy to over estimate the number of staves you could get from your log. Trust me, you’ll be much happier with 4, over sized, nice consistent staves than 5-8 with runout (if you’re really lucky). The posts that look like they could make 8 great staves often make 2, plenty of kindlin and disappointment. When cutting to length initially, the greatest amount of taper and curve is at the butt. Since every inch counts, the inches opposite the butt will generally be straighter but the rings are thinner. Hedge is the only tree that resists rot and insects, with bark on and standing upright. They can get destroyed (for bowyers) in many ways lying down. Unwanted twists and bends can be taken out, even by a newb, so try not to let little imperfections discourage you, including knots. Big nasty knots, in the handle area especially, can wind you up with an awesome lookin’ bow. Small knots don’t pose much problem at all as long as they are solid (lacking the black or pithy rot/ soft core). I’ll shut up now, going to grab my Grandpa’s ol draw knife and get into some of the best staves I’ve ever split out, now 5,6 years dry and stable.