I have to admit that I am an artist first and a bowyer second. Yes,…

How a recurve bow works

What is a recurve?

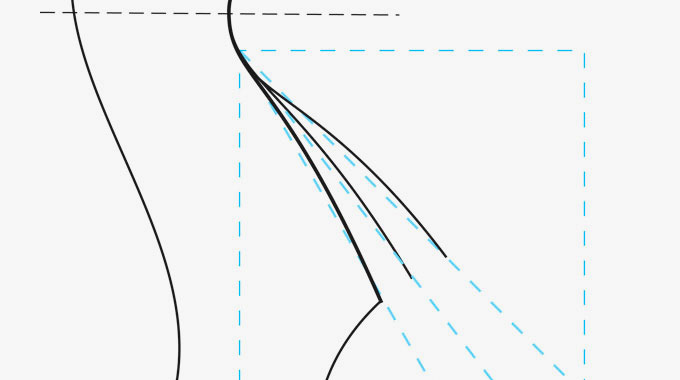

A recurve is simply a curved portion of the tip of the bow limb. Recurves can either be static (rigid) or working (bending). Many sizes and shapes of recurves have been tried throughout archery history, and are still very popular on modern bows. Most modern recurves can be called “contact recurves,” because the string “contacts” the recurved portion of the belly surface of the limb. On some contact recurves, the string will stay in contact with the belly surface of the limb all of the way from brace height until full draw. On other recurve designs, the string will lift off of the belly surface of the limb at some point during the draw. The length of draw where the string lifts off can dramatically affect the force draw curve of the bow. Typically, the later in the draw stroke that the string lifts off, the more energy the bow can store throughout the draw stroke and the smoother the draw stroke will feel.

A recurve creates the effect of a cam as the bow is drawn. Because of it’s tightly curved shape, a bow with recurved limb tips provides even more leverage for the string throughout the draw, which allows a recurve bow to store even more energy than a straight-limbed, reflexed, or even a reflex/deflex bow.

How a recurve works

While the string is contacting the belly surface of the recurve limb, the bow acts like it is a shorter bow. The bow behaves as if it is only as long as the distance between the two contact points of the string on the limbs. As the bow is drawn and the string lifts off of the recurved limb, these contact points become farther apart, and the bow behaves as if it is getting longer. This is the secret of how a contact recurve works…it is a short recurved bow that can be drawn as far as a longer, straight bow without losing leverage and without stacking.

Working recurve

A “working” recurve is one where the recurved portion of the limb bends or “works” during the draw cycle. As the bow is drawn and the recurve uncoils, the string lifts off of the belly surface of the limb. Again, this allows the limb to act as if it is longer limb, and allows it to maintain additional leverage at a longer draw length than a straighter bow. The optimum recurve shape is one where the string angle stays at a small angle at full draw, giving the string much more leverage on the the limb than a straight or reflexed limb tip. Whether the string lifts completely off of the belly surface depends on the shape of the recurved portion. Even though a working recurve uncoils some, it should never completely straighten out. During the power stroke, the working recurve coils back up and the string climbs back on to the belly surface of the limb, effectively shortening the limb again.

A “working” recurve is one where the recurved portion of the limb bends or “works” during the draw cycle. As the bow is drawn and the recurve uncoils, the string lifts off of the belly surface of the limb. Again, this allows the limb to act as if it is longer limb, and allows it to maintain additional leverage at a longer draw length than a straighter bow. The optimum recurve shape is one where the string angle stays at a small angle at full draw, giving the string much more leverage on the the limb than a straight or reflexed limb tip. Whether the string lifts completely off of the belly surface depends on the shape of the recurved portion. Even though a working recurve uncoils some, it should never completely straighten out. During the power stroke, the working recurve coils back up and the string climbs back on to the belly surface of the limb, effectively shortening the limb again.

Static recurve

A “static” recurve is one where the recurved portion of the tip does not bend and stays tightly curved during the draw cycle. As the bow is drawn, the recurve simply rolls over. Like a working recurve, the string typically lifts off of the limb some, but does not lift completely off of the limb. It usually stays in contact with the belly surface of the tip of the recurve at least some at full draw. Static recurves usually store a lot of energy and are very quiet when shot. I am guessing that the combination of a high preload at brace and the tightly recurved shape of the tips is what helps them reduce vibration and settle down quickly as the limbs come to a stop. Of course, if the bow limbs are balanced and the limb tips are light in weight, that helps too…but that is the subject of a different discussion. 😉

A “static” recurve is one where the recurved portion of the tip does not bend and stays tightly curved during the draw cycle. As the bow is drawn, the recurve simply rolls over. Like a working recurve, the string typically lifts off of the limb some, but does not lift completely off of the limb. It usually stays in contact with the belly surface of the tip of the recurve at least some at full draw. Static recurves usually store a lot of energy and are very quiet when shot. I am guessing that the combination of a high preload at brace and the tightly recurved shape of the tips is what helps them reduce vibration and settle down quickly as the limbs come to a stop. Of course, if the bow limbs are balanced and the limb tips are light in weight, that helps too…but that is the subject of a different discussion. 😉

Please share this post with your friends and leave a comment.

Comments (0)